By Randy B. Young

American sports reveal the best and worst of our American values. From the Chicago “Black Sox” to 1980’s “Miracle on Ice,” sports have held up a mirror reflecting both the beauty and ugliness in our nature.

By the rulebook, baseball is fair. It’s 90 feet down the baselines in Fenway Park or Yankee Stadium. Three strikes is an out in Portland or Peoria. These principles have conspired to maintain a level playing field for over 150 years. For too long, however, these “fair” playing fields were less-than-level for many. Whereas Jim Crow laws were imposed in the American South, prejudice was rampant even in the North—even in Connecticut.

“Historically, Connecticut’s hands aren’t clean, by any measure,” wrote Andrea Maria Black, daughter of the late Gil Hernandez Black, a Stamford native who played locally and with the Indianapolis Clowns.

From all-Black and integrated teams of the 1800s to segregated teams and Negro League players in the early 1900s, discerning an absolute history is problematic. Even the team names featured slight-of-hand: the New York Cubans had only African American players—no whites, and no Cubans.

Legend and Lore

“Baseball fans are junkies, and their heroin is the statistic,” author Robert S. Weider wrote in In Praise of the Second Season.

Baseball fans now ferociously follow teams. Early on, however, teams might emerge, thrive and perish in a year. During that span, a Black player might play for a dozen teams. Scores weren’t always written down, statistics were sketchy, and players’ deeds were often relegated to myth and lore.

“If baseball is America’s pastime, it has been Connecticut’s passion for more than 150 years,” says Steve Thornton, creator of the Shoeleather History Project, and one of the leading experts on Black and Negro League baseball in Connecticut. “Towns, neighborhoods, factories and churches all had their own teams—from the Hartford Dark Blues to the New Britain Aviators. The history of African American baseball is right under our feet in Connecticut. It’s like archeology: you discover a little, but then you find a little more.”

“African Americans began to play baseball in the late 1800s on military teams, college teams and company teams,” notes the Negro League Baseball Museum in Kansas City, Mo. “However, racism would force them from these teams by 1900. In response, Black players formed their own units, ‘barnstorming’ around the country.”

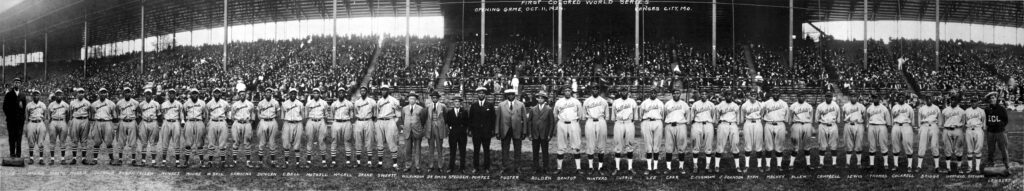

In 1920, responding to Jim Crow laws and resistance to integration, former player Andrew “Rube” Foster spearheaded the formation of an official Negro League for Black players. The League thrived during the Depression but began to disappear following Major League integration in 1948.

Blacks weren’t the only targets of prejudice, Thornton says.

“There were American Indians, Cubans and even Hawaiian players that played in Connecticut as well. If your if your skin was brown, you were in the second-tier league.”

“During spring training with the (Boston) Braves, all the Black players had to sleep on the porches of the buildings while white players slept inside,” states Hernandez Black at a Connecticut Library “Third Thursday” appearance in 2018 (he died in 2023).

“In cities and small towns all across the country, there were African American teams and Black stars that may have been the greatest of the century, but whose deeds would live only in the memories of those who saw them play,” explains Ken Burns in his documentary Baseball.

But fans were watching—even white crowds—drawn by the love of baseball and style of play exhibited by Black stars, which Burns notes was “faster, more daring than that in the Majors, and just as competitive.”

Hitting to All Fields

Black history in Connecticut baseball begins early on with players’ growing reputations for talent and spectacle after the Civil War.

Baseball Hall of Famer Ulysses “Frank” Grant, for example, was perhaps the best Black player in baseball in the 1880s. After playing with local semi-pro teams in Pittsfield, Mass., and in Plattsburgh, N.Y., Grant joined the team in Meriden, Conn.

Grant and Moses “Fleetwood” Walker played for integrated Meriden, Ansonia and Waterbury semi-pro clubs,” Thornton said.

Born at a waystation on the Underground Railroad according to one biographer, Walker played for the Waterbury (Conn.) Brassmen and was the first African American to cross over to the Major Leagues prior to segregation.

After 1920, new standouts emerged through the Negro Leagues, including Satchel Paige, Jackie Robinson and even 1933 Hartford Bulkeley High graduate Johnny “Schoolboy” Taylor. Taylor traveled the semi-pro circuit, pitching for Hartford’s Savitt Gems at Hartford’s Bulkeley Stadium and a Yantic team and later signing with the New York Cubans.

Connecticut baseball fans didn’t discriminate when it came to attendance, however.

“Working people took the days off in the middle of the week and packed Hartford’s South End Stadium with 4,000 fans,” Thornton said. “Connecticut was baseball crazy anyway, and to see the Black players play was something to behold.”

A Wink and a Nod

While baseball was celebrated in Connecticut, Jim Crow was still the law of the South and northern sentiments, if not codified, echoed the same prejudices.

“Some teams simply wouldn’t play if there was a Black player playing,” Thornton says, explaining that the Major League Baseball Commissioner and team owners had a gentlemen’s agreement—a wink and a nod—not to allow Black players into the Majors.

“Black players had to find a dressing room at some facility that wasn’t near the baseball field,” Thornton adds. “Players that played in the south end of Hartford had to travel back and forth by trolley just to get dressed.”

Long rides to games were common, says Hernandez Black, “…and if you missed the bus, your team might be (hundreds of miles) away.”

“Black ballplayers in this state established a proud tradition of excellence,” Thornton continues. “Still, an understanding of America’s game is not complete until fans know the names of Frank Grant and Moses ‘Fleetwood’ Walker just as well as they know Ted Williams and Mickey Mantle.

Without certified results or reliable statistics for Black players and teams, historians must scour the oral histories. Where record books fail to paint a true picture, the best (and tallest) tales and legends came the players themselves.

Negro League standout and Major League Hall of Famer Leroy “Satchel” Paige once worked as a train station porter, toting bags of wealthy passengers, and resembling a “walking satchel tree.”

Paige once said of “Cool” Papa Bell that he was so fast he could flip the light switch and be in bed before the room got dark.

Similar attributions follow Norman “Turkey” Stearns (who ran like a turkey), Ernest “Boojum” Wilson (whose hits pounded outfield walls with a loud “Boojum”), Arthur “Rats” Henderson (co-workers once hid rats in his lunchbox) or George “Mule” Suttles (who would kick 600-feet home runs like a mule).

What If…

Like America itself, baseball is about hope and second chances. Another game, another time at bat…another chance to finally get things right.

In 2020, on the 100th anniversary of the Negro Leagues’ founding, Major League Baseball began research to incorporate the statistics of more than 2,300 Negro Leagues players from 1920 to 1948, officially adding achievements of Negro League players to its official historical record … “correcting a longtime oversight.”

The initiative still doesn’t account for players for Black or integrated teams in the 1800s, nor does it account for players on barnstorming teams in the early 1900s.

“Systematically for six decades, Black Americans were excluded from playing (in) the organized wing of America’s pastime,” says writer Daniel Okrent in Ken Burns’ Baseball. “What we are left with…is memory, legend, and an endless series of ‘What if’s.’”

A graduate of Dartmouth College, Randy B. Young worked in advertising in New England before relocating and working in communications for the University of North Carolina in Chapel Hill. N.C. Recently retired, he is a freelance writer and photographer.

More Stories

Winter Wellness: Simple Ways to Feel Your Best All Season

A Hallmark Movie Featuring Slightly Old Folks

Hartford and Raleigh: A Tale of Two Hockey Hubs